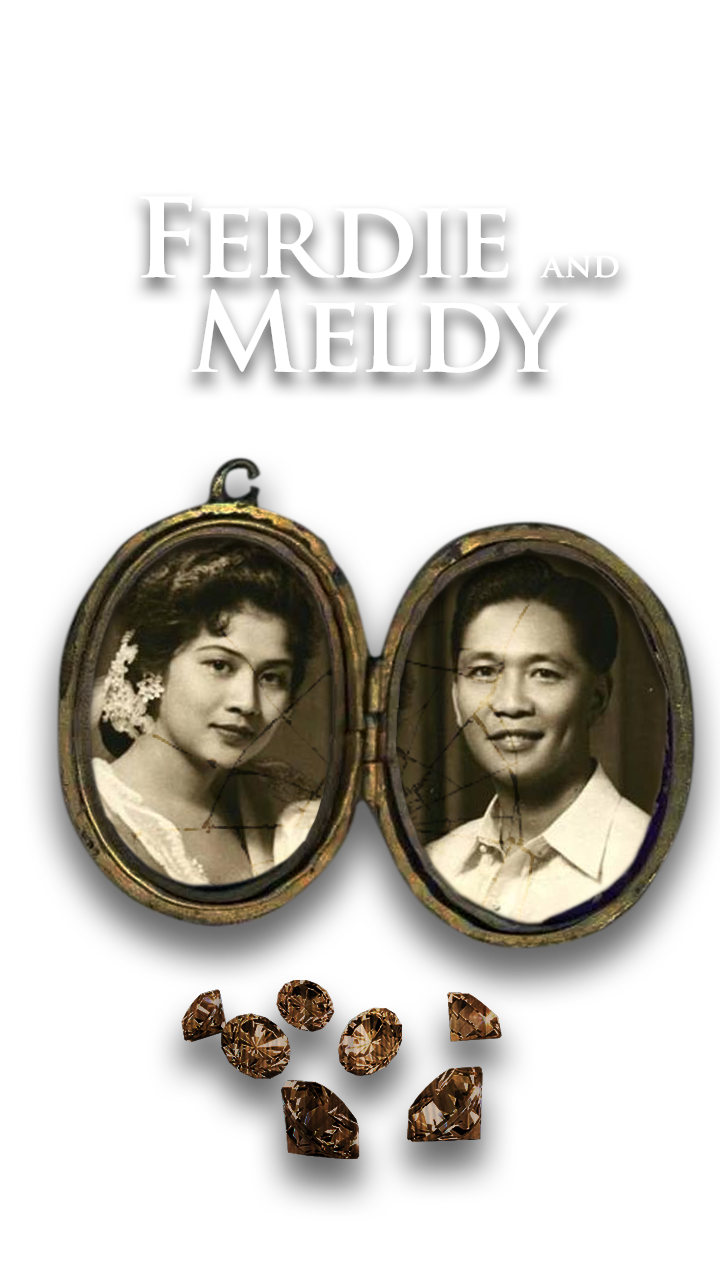

This series of stories begins with a match made in hell: the story of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos, which led to the conjugal dictatorship that plunged our nation to the dark days of Martial Law.

But love, too, played a great role in the resistance. The next two stories tell how two couples’ love for the nation and the masses led them to love one another.

For Edna and Alex Aquino, it blossomed at the frontline of the underground movement against the Marcos Regime.

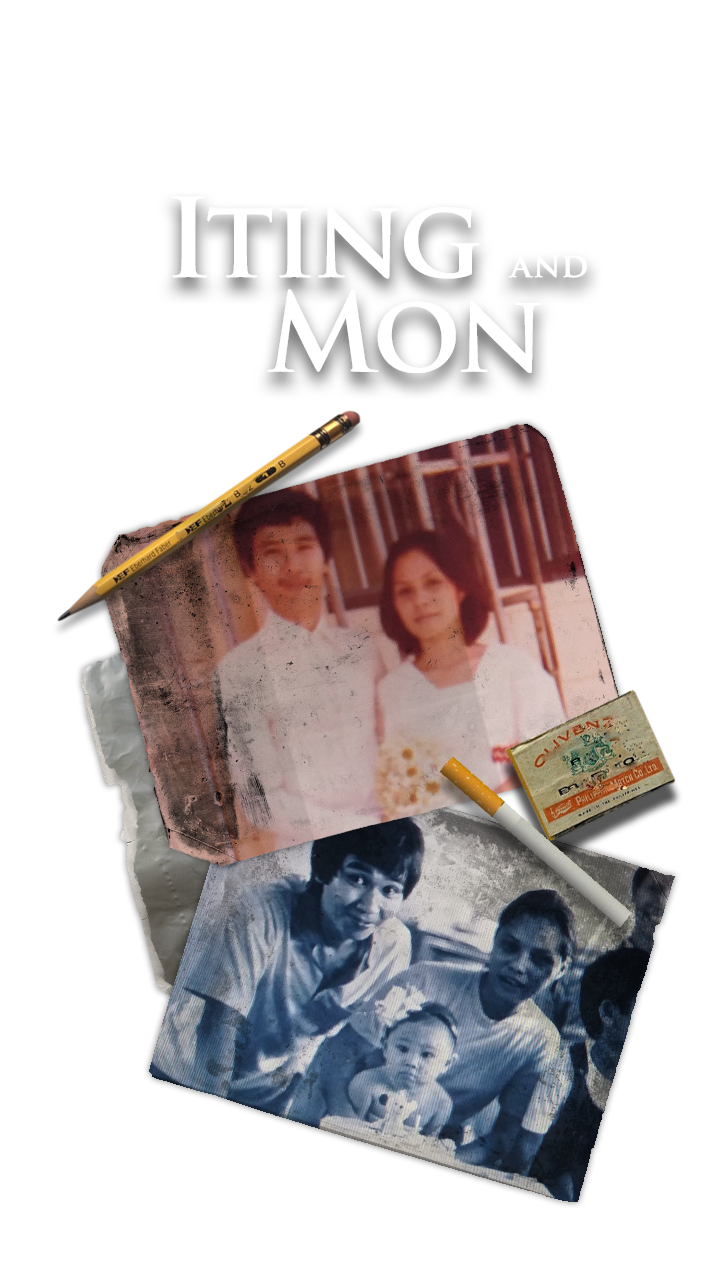

For Mon and Iting Isberto, it was ingenuity and determination that kept them together, from their previous long-distance relationship to their separation during solitary confinement.

One pair plundered the country, and two fought back. Read all three stories here.

To view the stories, swipe left-right, and up-down if you are using a mobile device.

Use the navigation arrows on the screen and keyboard keys if you are on a desktop.

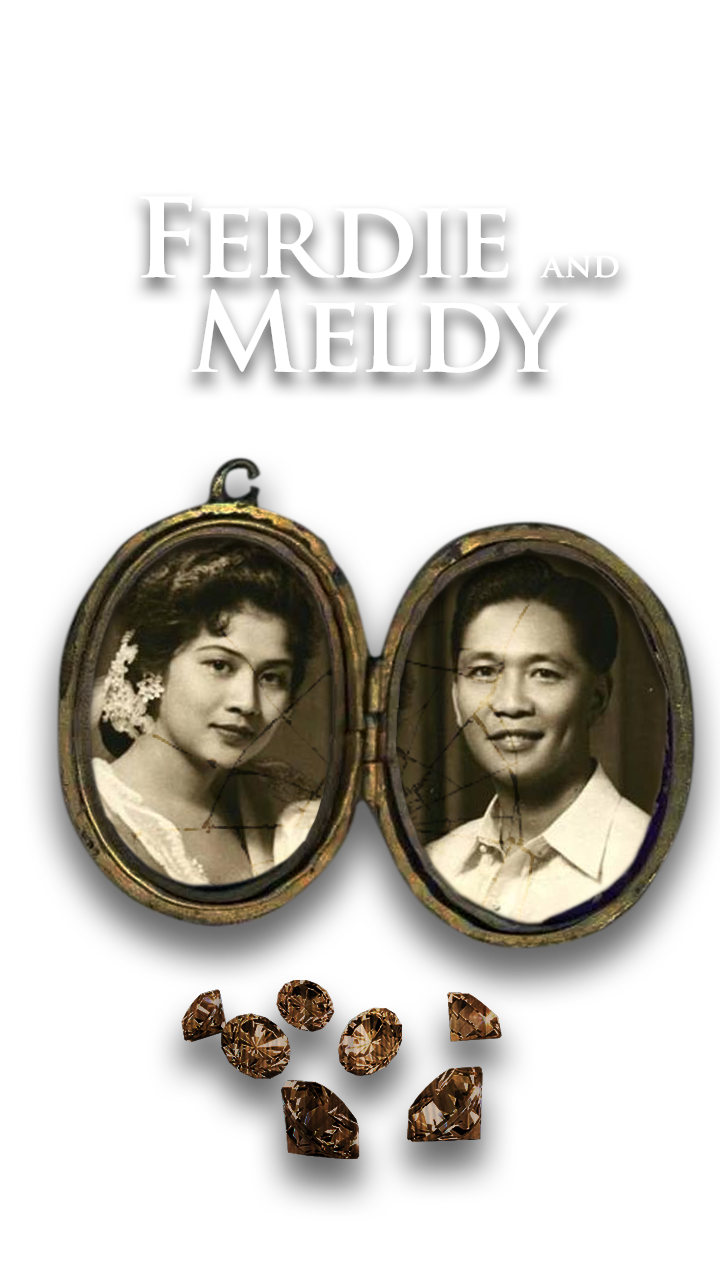

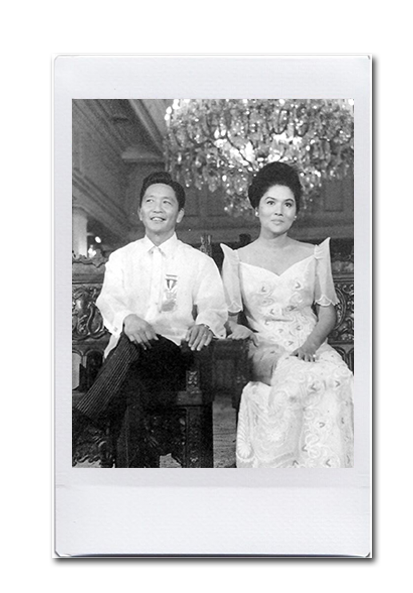

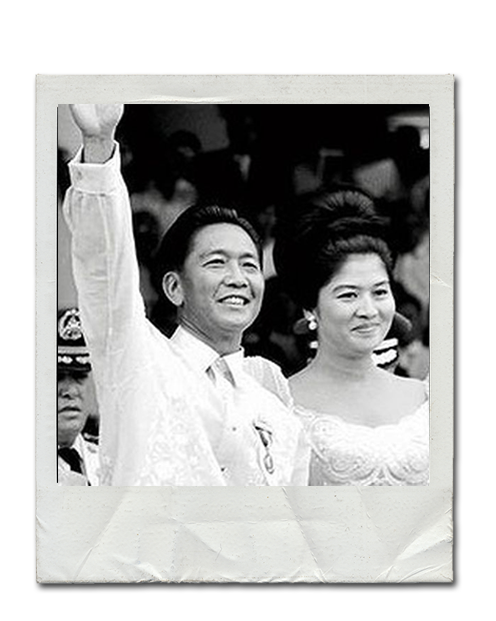

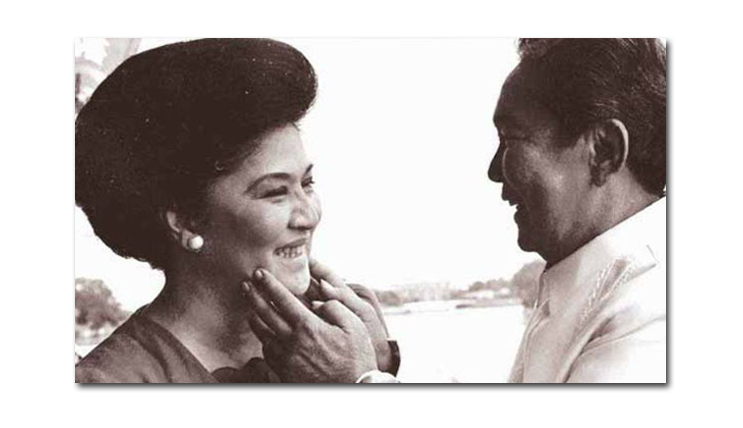

Late one evening in 1954, Imelda Romualdez and then-Rep. Ferdinand Marcos of Ilocos Norte crossed paths at the Manila Capitol. It was “love at first sight,” according to the young Ilocano, who was then a rising congressman and known for being a womanizer.

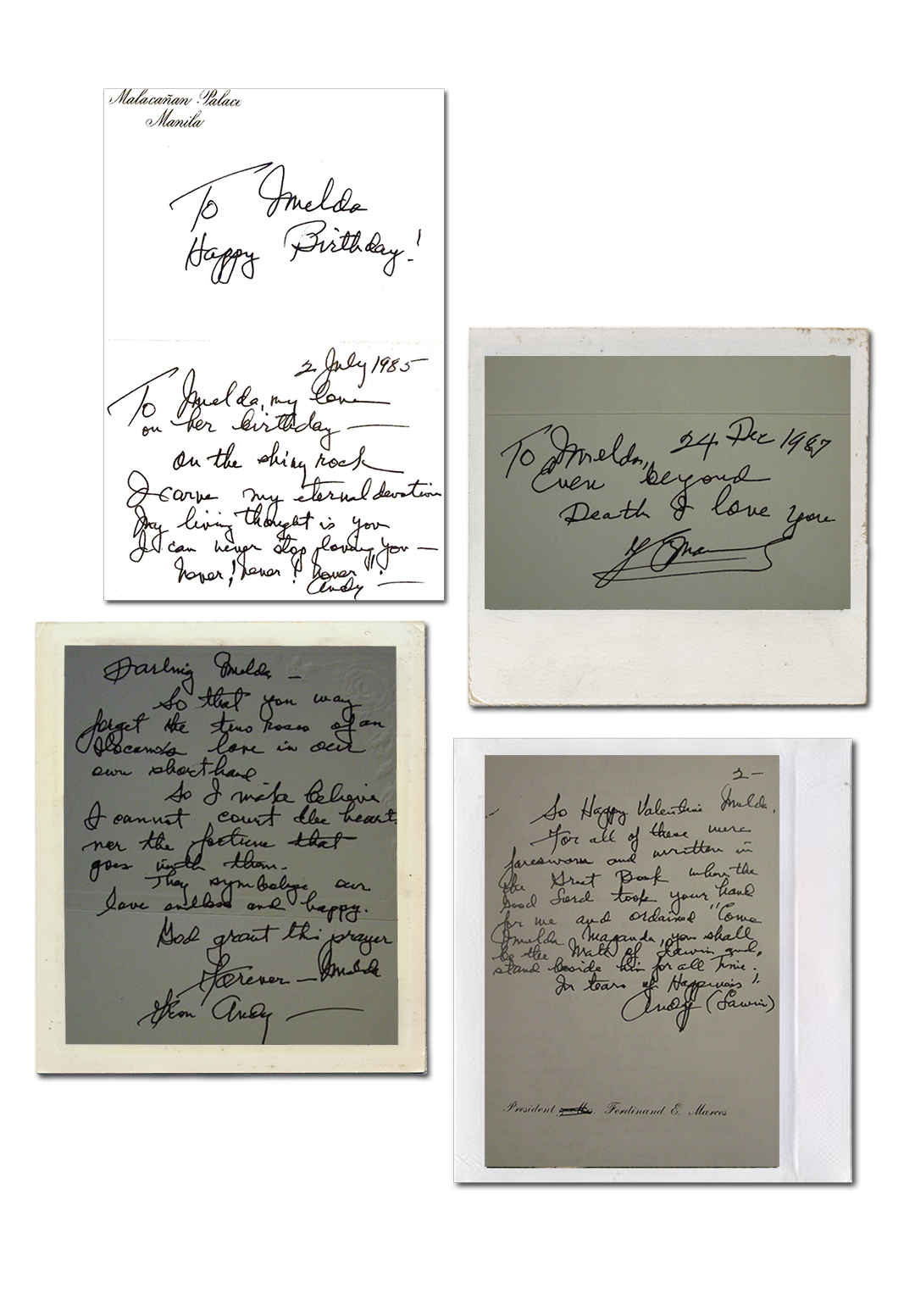

The next day, Imelda received two red roses from Ferdinand “one in full bloom and the other in tight bud” —with a short note saying, “Everything is so rosy. I wonder why.”

Imelda learned that in Ilocano courtship custom, “the bud denoted her tightly closed un-awareness of what was about to blossom, while the open rose symbolized his mature love and flat declaration of marriage.”

Only after 11 days of courtship, starting from the night they met, Imelda and Ferdinand got married in Baguio City.

Gifts of Love

San Juanico Bridge

With more than three years of construction costing around $22 million at the time, this iconic structure is dubbed as one of the symbols of Ferdinand Marcos’ love for Imelda. Also called as the Marcos bridge by their loyalists, this bridge was inaugurated on July 2, 1973, in time for Imelda’s 44th birthday. One of the longest bridges in the country, San Juanico Bridge connects Leyte — the birthplace of Imelda — and Samar.

Ironically, one of the torture methods used during the Marcos regime was named after the bridge.

Cultural Center of the Philippines

Founded in 1969, the development of the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) took three years to build. This brainchild of the Marcoses was born out of their desire to emphasize the promotion and preservation of Filipino arts and culture. It is believed that Imelda was highly involved in this project and it remains her “most ambitious fundraising venture to date.”

New York Buildings

Ferdinand’s love for Imelda is not just known in the Philippines — it also made the headlines of International newspapers in 1986 when he was exposed to giving four New York buildings as a gift to his wife. These properties, which are worth more than $300 million, were located at 730 Fifth Avenue, 40 Wall Street, 200 Madison Avenue, and Herald Center at Herald Square.

While the infamous couple denied the allegations of owning these properties, the matter has become an issue during the 1986 snap elections in the country as their family has been accused of grave corruption.

Love Letters of Ferdie to Imelda

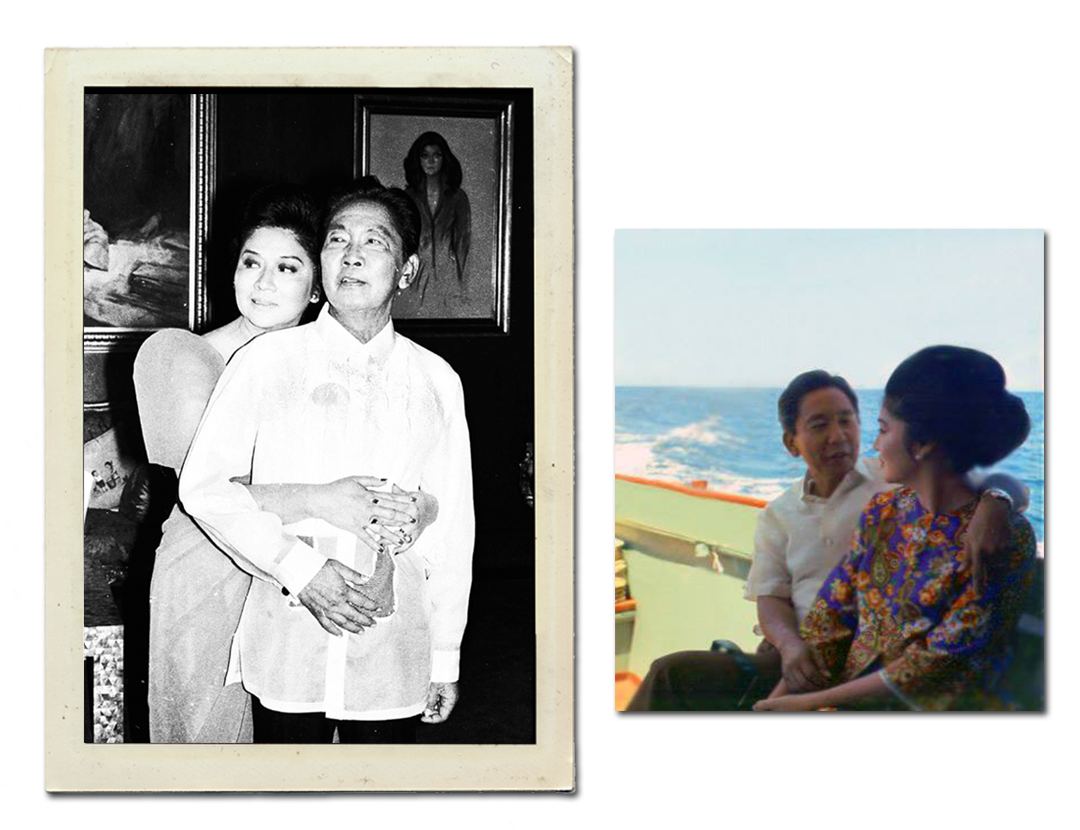

The King and The Kingmaker: The Marcoses’ Shared Greed for Power

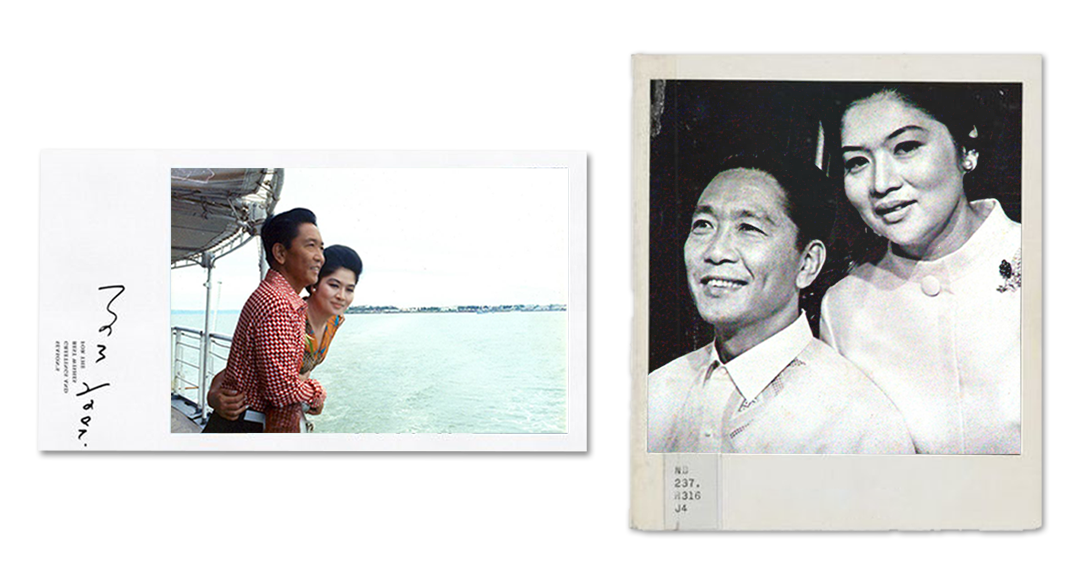

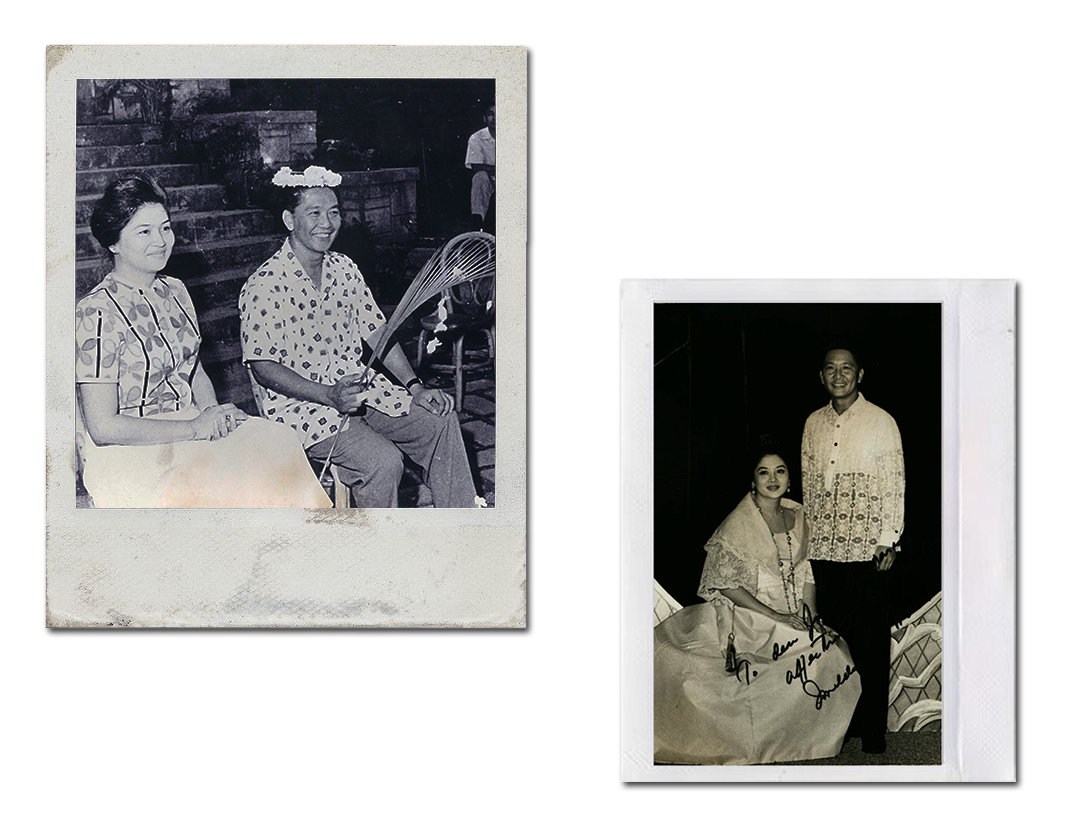

More than what they call love, Ferdinand and Imelda shared another thing in common: greed for power.

Since Ferdinand first assumed the presidency in 1965, Imelda had not stopped meddling with presidential affairs. With the “kingmaker” herself always sticking her nose to her husband’s business, it is no doubt that everything about their marriage is conjugal — from sharing the country’s chief executive powers to taking part in their family’s dictatorship during the Martial Law period.

Major appointments concerning the late President have to be cleared by the First Lady, or else the appointee would suffer harassment due to Imelda’s disappointment. It also came to the point when Ferdinand had to make policies to appease his wife’s demands.

More than this, Imelda — as a strong woman she claims to be — conditioned the mind of her husband that he was nothing without her; that he must always give what his wife’s lavish demands. Of course, the kingmaker’s expensive requests took a toll on every Filipino taxpayer’s money, and their shared greed for power continues to make us pay their debt until today.

Alvarez, L. (2011, July 14). The cultural center of the Philippines, home of Filipino culture and arts. Retrieved February 28, 2021, from https://www.wheninmanila.com/the-cultural-center-of-the-philippines-home-of-filipino-culture-and-arts/

Edifice complex: Building on the backs of the Filipino people. Retrieved February, 2021, from https://martiallawmuseum.ph/magaral/edifice-complex-building-on-the-backs-of-the-filipino-people/

Gerth, J. (1986, January 30). 4 new YORK buildings CALLED Marcos gifts to wife. Retrieved February, 2021, from https://www.nytimes.com/1986/01/30/world/4-new-york-buildings-called-marcos-gifts-to-wife.html

Guzman, N. (1970, January 01). The mysterious curse of the manila film center. Retrieved February, 2021, from https://www.esquiremag.ph/long-reads/features/manila-film-center-haunted-a1729-20191107-lfrm2

Institutional profile. (n.d.). Retrieved February, 2021, from https://www.culturalcenter.gov.ph/pages/history

Marcos, I. (2018, September 11). Retrieved February, 2021, from https://www.facebook.com/ImeeMarcos/posts/ferdinands-love-letters-to-imeldaferdinandmarcos-fm-apolakay-september11-101-ime/10156751809132431/

Mijares, P. (1976). The Conjugal Dictatorship. Union Square Publications: San Francisco

Pedroso, K. (2014, September 21). ‘San Juanico Bridge,’ OTHER tortures Detailed. Retrieved February, from https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/639646/san-juanico-bridge-other-tortures-detailed

Person. (2019, July 07). That will be one Million Pesos, please! Retrieved February, 2021, from https://www.philstar.com/lifestyle/health-and-family/2019/07/09/1933008/lifestyle

Quirante, N. (2018, March 25). San Juanico bridge, a symbol of love. Retrieved February, 2021, from https://pia.gov.ph/news/articles/1005720

Richburg, K. (1986, April 10). Real estate agents tell of Marcos Buys. Retrieved February, 2021, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1986/04/10/real-estate-agents-tell-of-marcos-buys/5a674a66-2f9f-48d7-b076-223bdf8c5888/

“It wasn’t easy, but it was worth it”

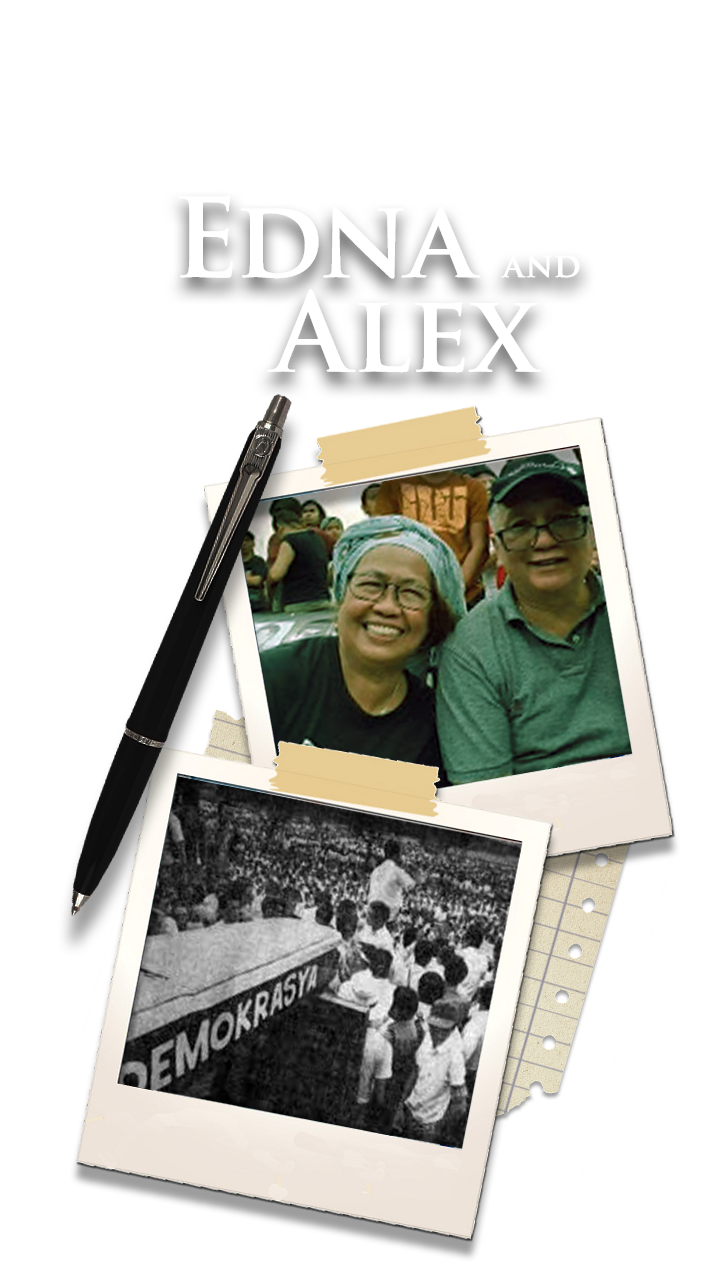

— Edna and Alex Aquino can tell that much about their marriage. A couple for 49 years, theirs was a love that bloomed at the frontlines of a long and dangerous struggle.

Edna Aquino at EDSA 1986 together with Ecumenical Concerns for International Concerns group.

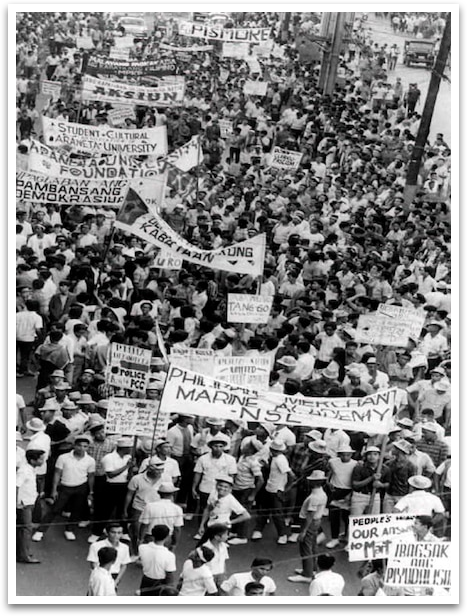

Edna, a scholar at the Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila (PLM), took part in what came to be known as the First Quarter Storm of 1970. “It was then, as I was struck by a truncheon, that I came to know what fascism was,” she says.

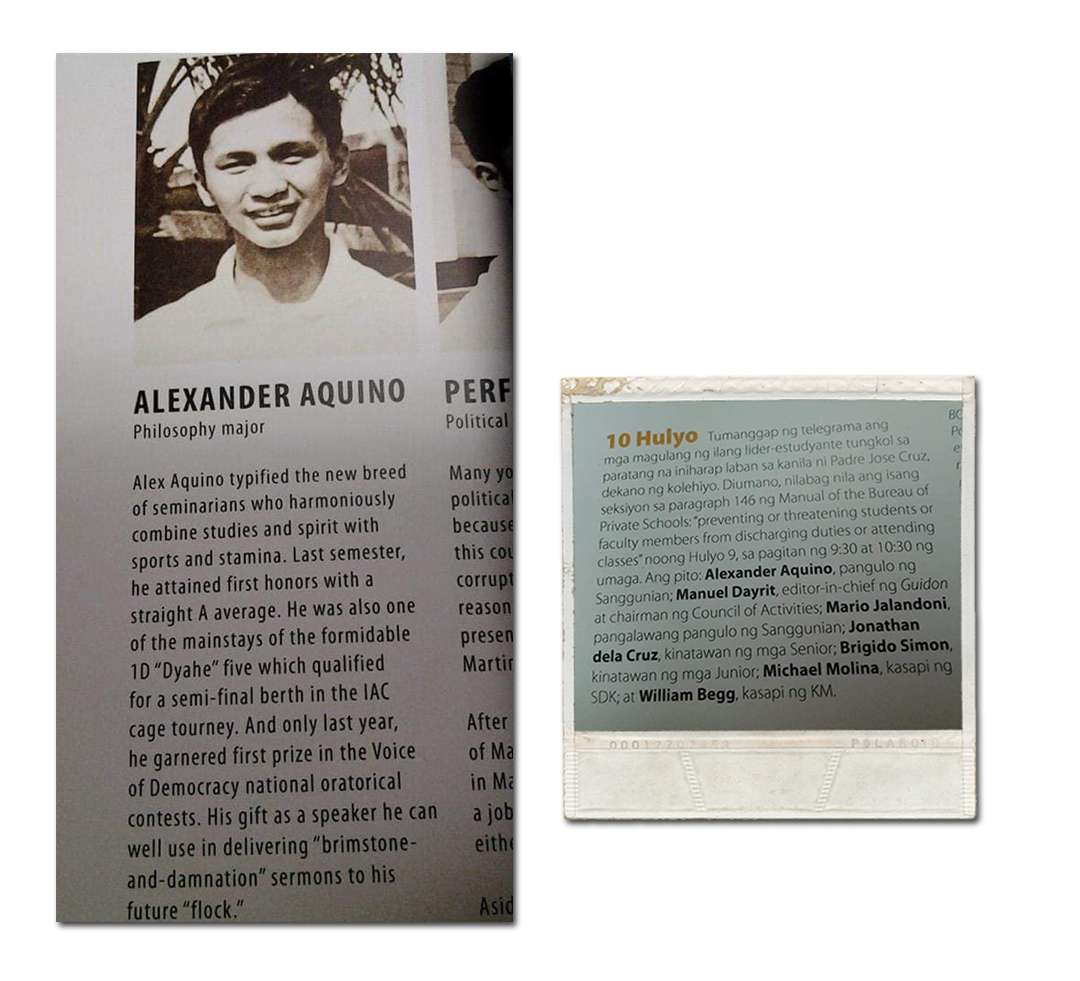

Alex Aquino as Student Council President of Ateneo De Manila University (ADMU).

Alex had his first brush with activism as a seminarian at the Ateneo de Manila University (ADMU). His parents, both lawyers, had instilled in him “a strong sense of right and wrong.”

It was against the backdrop of the looming dictatorship where the young rebel found his cause.

Because the bureaucrats who ran the schools were wary of dissent, both Alex and Edna were expelled from their universities. They were forced to join the underground movement against the Marcos Regime. It was in the thick of it where their two stories would come together.

In the movement, they were assigned to be each other’s “buddies” who would look out for each other as they moved from house to house, staying under the radar of the military and police. What was first a survival tactic became a close friendship. And then they fell for each other.

They lived two lives: one underground, and on “on the surface.” As they carried on with their activism, they also became parents to three children. Alex was jailed—twice. While the nature of their work often separated them from each other, they shared parental responsibilities and made every decision together.

Today, we are caught in another era of uncertainty and unrest. What can this relationship teach us?

“I don’t want to paint a rosy picture of it,” says Edna. “It came at a price. There were tears, quarrels, and ill will. There were ups and downs. But it was all part of our growth.”

Alex and Edna Aquino in their 49 years of relationship.

In the end, what kept and continues to keep them together is their love for humanity. “If you want justice, you start with the homefront.”

Indeed, the fight for social justice and democracy is often a grim affair — more so in times like these. But if we think beyond ourselves, as Edna and Alex did, there will always be a reason to keep going. There will always be hope.

In 1977, Ramon (Mon) and Ester (Iting) Isberto were both detained at the Bicutan Rehabilitation Center in Taguig. Mon would wake at four every morning in his cell and would begin to whistle a tune. From the opposite side of the block, Iting would answer through a song.

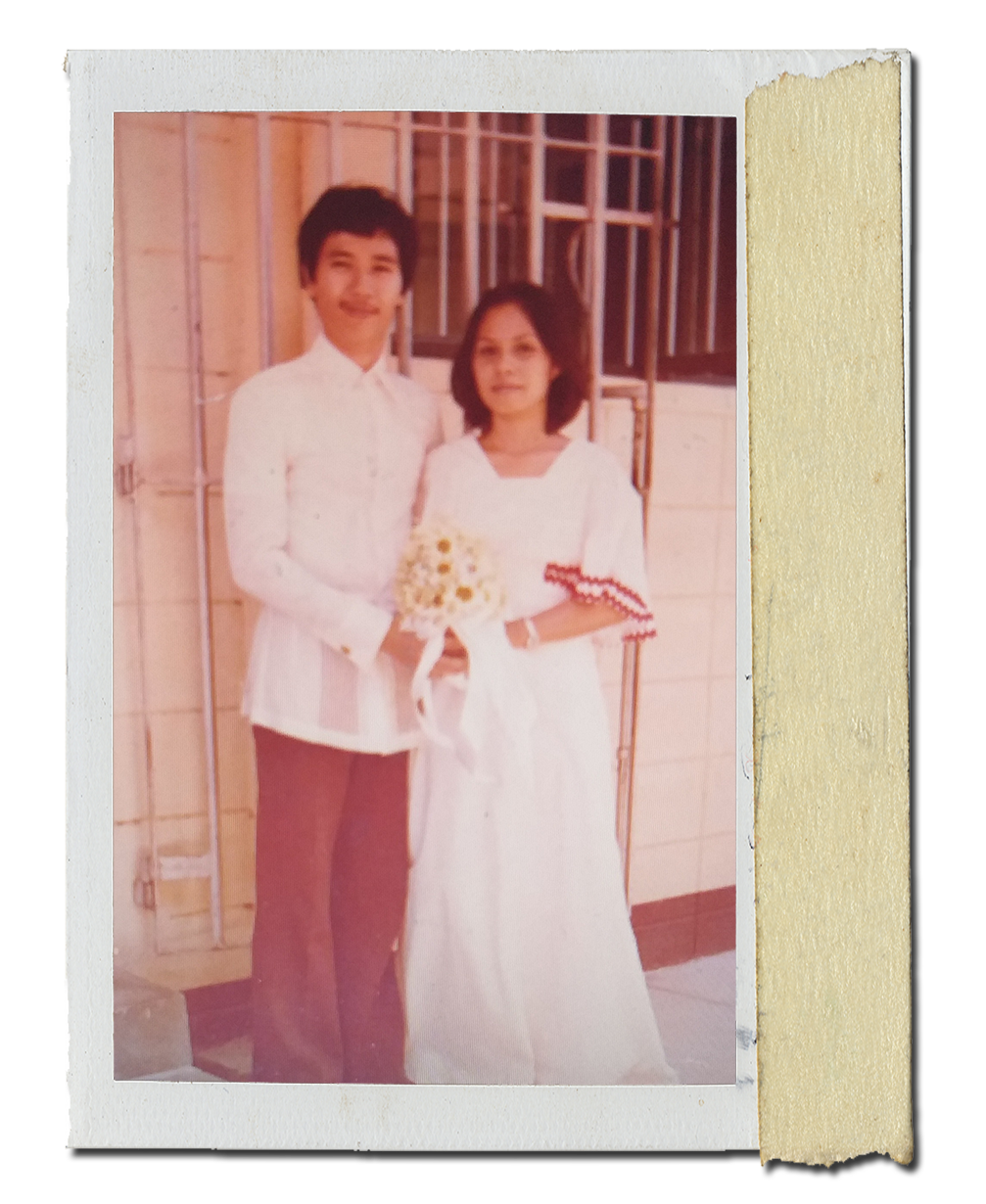

Iting and Mon Isberto’s wedding in Bicutan (1978).

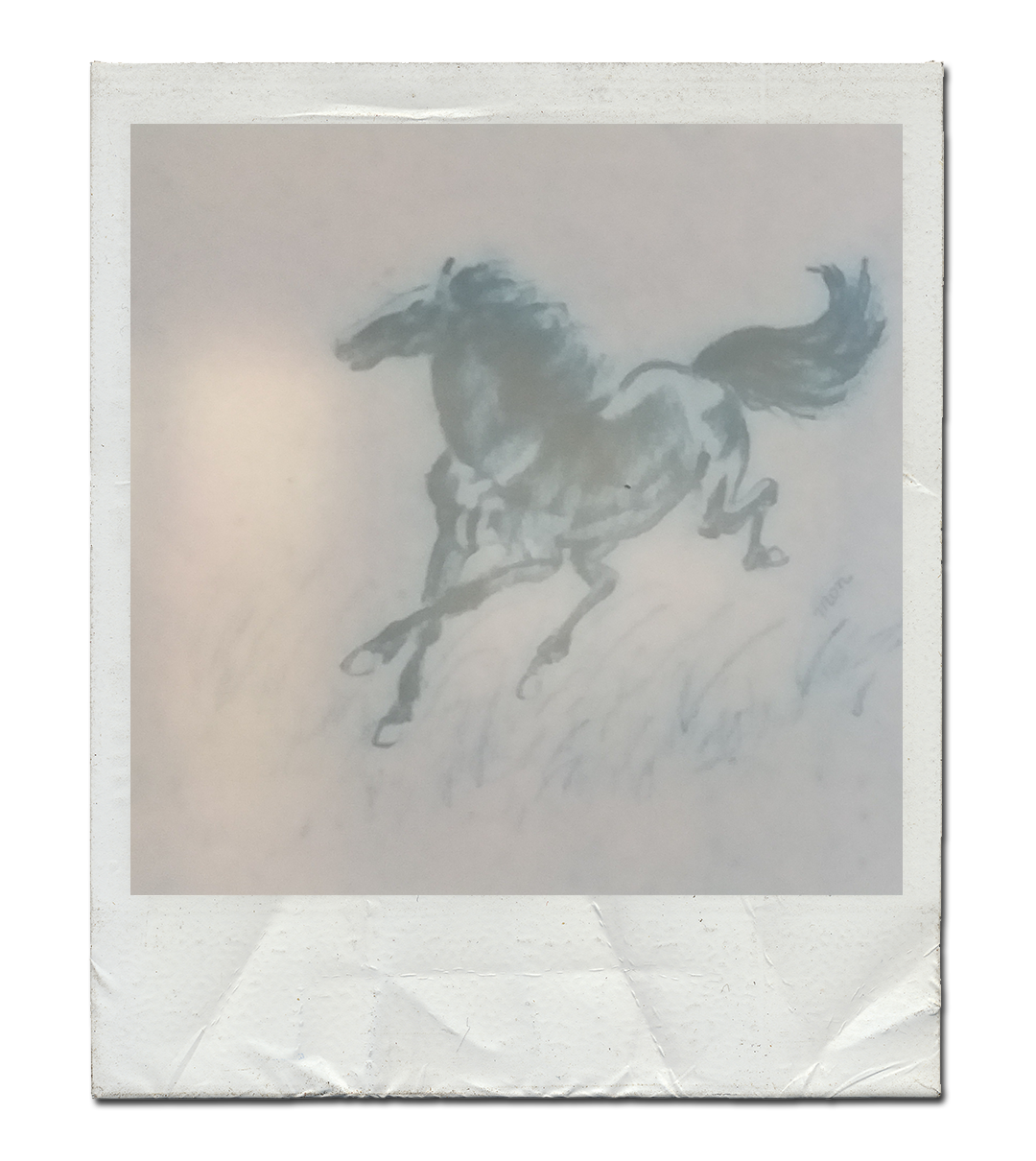

Mon’s drawing during his isolation on the 2nd floor of the Bicutan criminal building (1978).

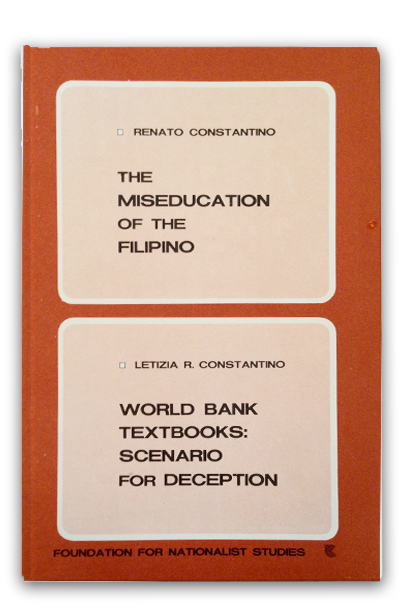

It was a hallmark of Mon and Iting’s love: to keep in touch against the odds. As college students in the 70s, while Iting was in Cebu and Mon studied in Ateneo De Manila University, they maintained a long-distance relationship through snail mail. Mon would send her his readings, including Renato Constantino’s The Miseducation of the Filipino, and wrote about his growing involvement with activism: first by educating himself, and then by joining campus protests.

Because Iting wanted to get to know her boyfriend better, she strove to understand the papers Mon sent her. His seeming obsession with social issues led her to question if she, in fact, had found the right person. “But then I realized,” she says, “that this Constantino was being truthful.”

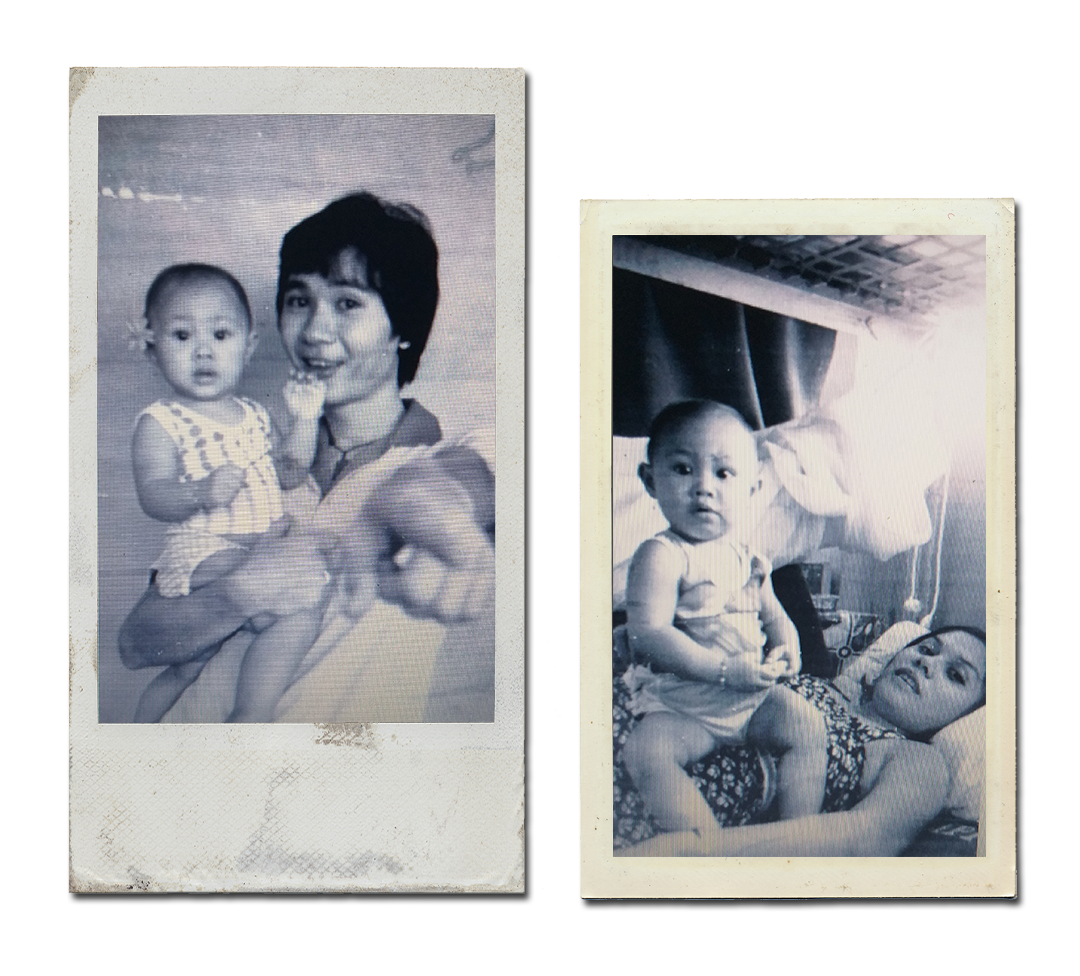

(L)Mon carrying 8-month old Mai during the visitor’s day visit in Bicutan prison (1979).

(R)Mai sitting atop of Iting at Mon’s “tarima” — the name the political detainees used for their small space. They used to hang blankets from the ceiling to make a small room for themselves.

Her own involvement with her theater group in Cebu—that campaigned for Cebuano plays to be shown in place of foreign ones—led her down the same road. Under Martial Law, a three-month detention at Camp Lapu-Lapu led her to meet more activists from Mindanao and the Visayas. When Mon went underground, Iting later traveled to Manila to join him.

The Horse – Another drawing of Mon in isolation at the 2nd floor of Bicutan criminal building.

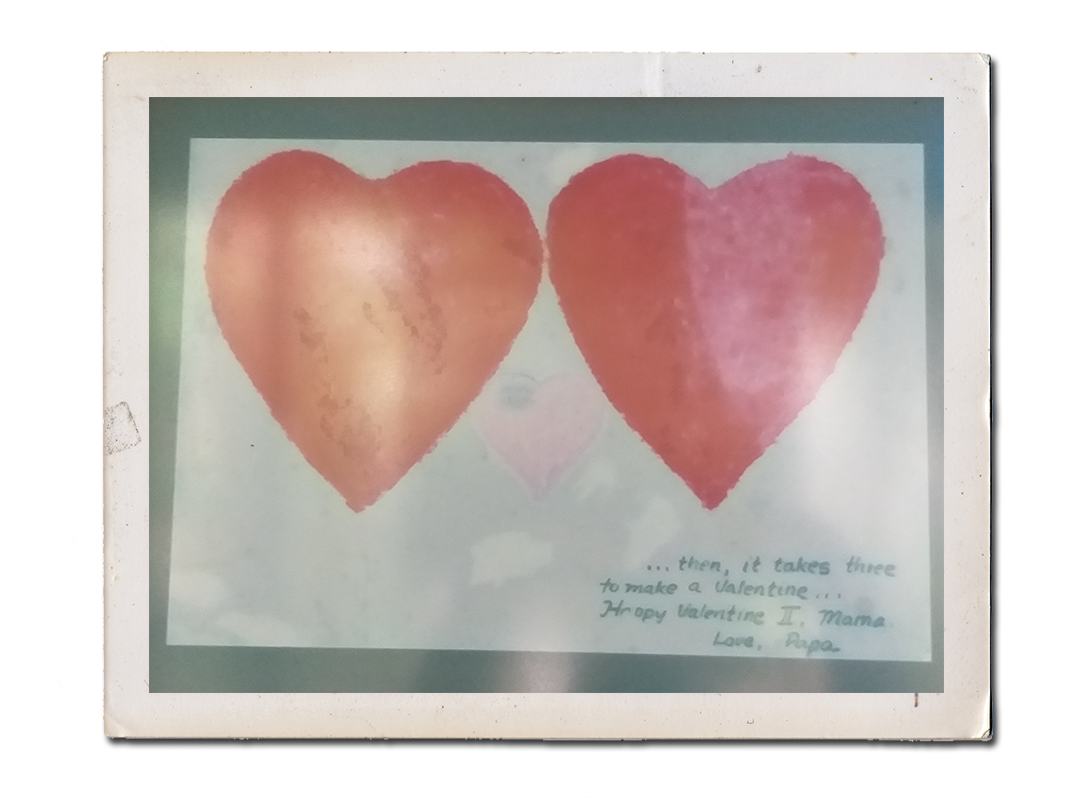

In 1977, they were put into solitary confinement at the same compound, where they scrawled letters to each other on the foil paper from packs of cigarettes. Friendly political detainees confined from the ground floor cells helped ‘mail’ the letters through a system that involved matchboxes and prearranged signals.

Iting, carrying their daughter, Mai while talking with Cardinal Bruno Torpigliani, the Vatican’s Papal Nuncio to the Philippines during the latter’s visit to the political detainees in Bicutan prison who were on hunger strike (1980).

Martial Law was a dark time and—one can argue—so is the present, with history poised to repeat itself. In the midst of uncertainty, how can we keep fighting?

“Live by the day,” says Mon. “Take life as it comes. If you get to wake up for one more day, be grateful.”

Despite the struggle, “I was happy I got to be with Iting,” he adds.

“If something happens to you, there’s a reason for it,” says Iting. “We are better people for what we went through. Everything we learned, we pass on to our children and grandchildren.”

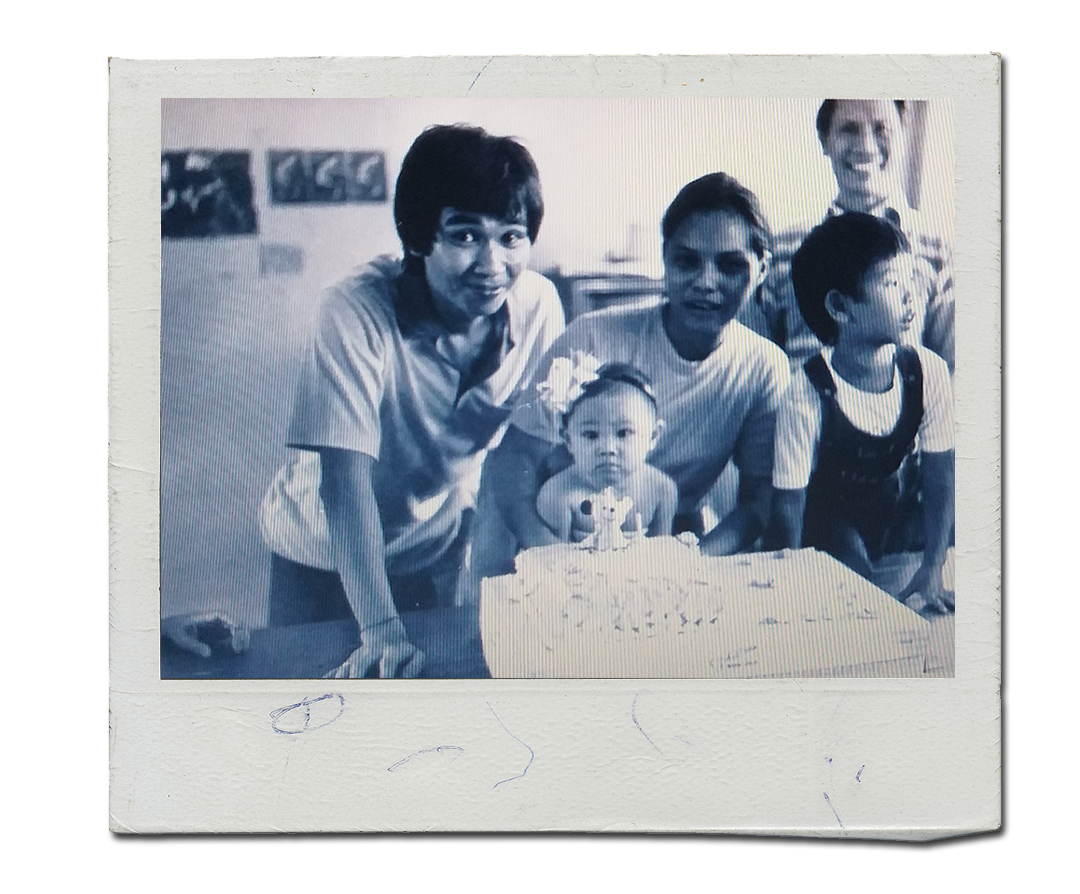

Mai’s first birthday celebrated in Bicutan. Leandro, Mon’s father, was standing behind the family.

“If you can help others,” she counsels, “then help them.”

Keeping in mind that Mon and Iting have been a couple for 46 years, it’s all sound advice for those whose love flourishes even in these trying times.

To commemorate People Power is not just to remember how we oust a dictator, it’s also to remember that the people who held hands in EDSA are ordinary people like me and you – people who feel grief, hunger, rage, and most importantly, love.

With love as our fuel too, let’s continue to challenge ourselves to be a part of the change. Let’s harness its power to awaken our inner heroes and to unite against those who threaten our peace and our rights, just like what we did 35 years ago. We need it now more than ever.

In memoriam

Dedicated to the memories of Lorenzo “Lory” Mendoza De Vera, a fearless advocate for human rights, labor rights, and the environment, a youth leader, a loving friend, and a true #LahingDakila. His passion in making the world a better place has inspired all of us to best our own fights. As we celebrate People Power, we will continue to ignite against the dying of the light, against those who threaten our democracy and our freedoms.

Resources

Martial Law Library (Upcoming)

Copyright 2021 | Digital Museum of Martial Law in the Philippines

Built and Designed by DAKILA Philippine Collective for Modern Heroism and Active Vista

Copyright 2021 | Digital Museum of Martial Law in the Philippines

Built and Designed by DAKILA Philippine Collective for Modern Heroism and Active Vista